Why Errors in Food Intake Matter

What is the big deal about errors in food intake in studies most people never hear about? It’s a problem because decisions on gaps in the diet, impact of nutrient intake, and the potential benefit or hazards of food and supplement intake are based on studies that use these techniques. I’ll give you a couple of examples, but let me start with something that has become common knowledge.

Obese subjects underreport food intake at a greater rate than subjects who are normal weight. Female obese subjects are more likely to underreport food intake than male obese subjects. Don’t assume they intend to deceive; I think many people are simply unaware of how much they eat, especially when they graze or sample food as they eat, pick at the kids’ leftovers, or eat little snacks at work.

Diet Change and Heart Disease

The Women’s Health Initiative is one of the largest studies done on examining the role of diet and heart disease in women. Results published in 2006 demonstrated that after a number of years on a low-fat diet, there were no differences in the rates of different forms of heart disease. What struck me at the time was that the goal was to reduce fat intake to 20% of total caloric intake, but using a form of dietary recall, the experimental subjects were able to lower their percentage fat intake from 35% down to 28%. That’s still much higher than the goal of 20%. If we were to estimate an average error in food intake based on dietary recall, it could very well be that these subjects actually had well over 30% fat intake due to under-reporting.

Why is that a big deal? Two reasons. First, they were not on a diet that was designed to reduce fat intake enough to impact cardiovascular disease. Second, in a review just published in 2021, a scientist is calling for the repudiation of the results of that study claiming that a low-fat diet does not work to reduce heart disease (or type 2 diabetes either). Based on the results of that WHI trial, we don’t know that for sure because of the potential for under-reporting food intake including fat, as well as the inability of the subjects to meet the goal of 20% fat in the diet. One error begets more errors. In this case, it’s being used to suggest that low-fat diets are not the way to reduce heart disease, and I’m just not ready to make that leap.

Nutrient Studies

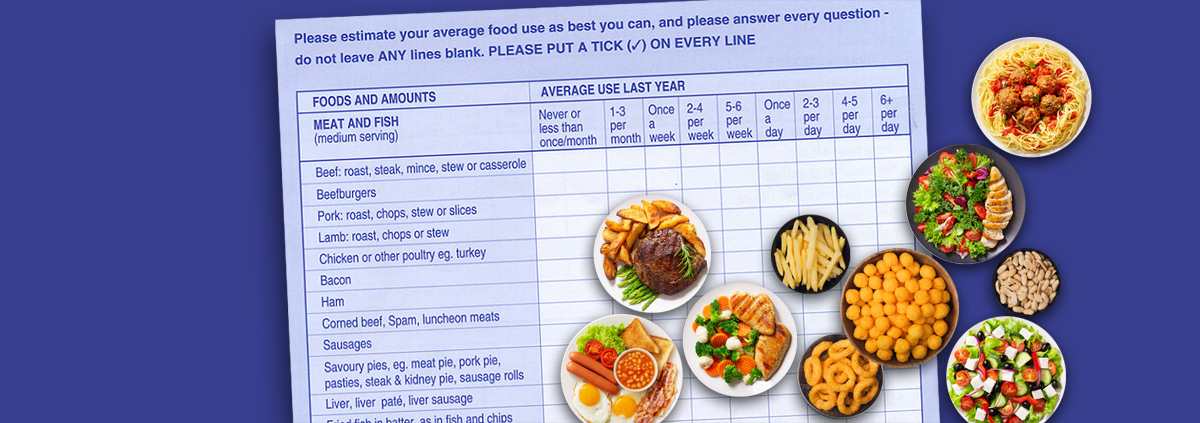

There are a number of studies that have used FFQ as the method of assessing food intake in individual nutrient trials. Aside from the “How many portions of beef did you eat per week over the past year” type of questions, the total number of questions ranges from 138 to 164 on most FFQs. The degree with which people will report that accurately is suspect to begin with. Add to that the potential under-reporting of food intake when you’re trying to assess iron, calcium, folic acid, and other nutrients in the diet can provide significant errors in determining how much nutrients people are getting. As the saying goes: garbage in, garbage out.

One more thing. The FFQ were validated by three-day diet histories, which are also prone to significant error.

The Bottom Line

Research that examines dietary intake may be prone to errors. It doesn’t make it worthless; it just means we have to interpret the results carefully. This is especially true when determining whether any specific diet can help reduce disease or prove whether a nutrient is beneficial or not.

What we can do is speak in global terms. Eat better. Eat less. Move more. Do that first and worry about the details later. Even with the potential errors in assessing food intake, there’s no question about that.

So here’s what I challenge you to do: for the next month, make a strong effort to eat better than you do right now. I think if you take this first step, you’ll feel the difference.

What are you prepared to do today?

Dr. Chet

References:

1. Front. Endocrinol. 2019. 10:850. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00850

2. JAMA. 2006;295:655-666.

3. Open Heart 2021;8:e001680. doi:10.1136/openhrt-2021-001680